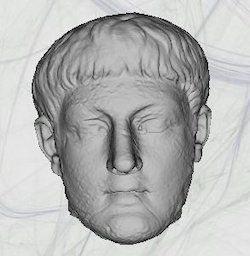

Click on the image to view the model. Download model as PLY

The head of Michaelis no. 202 has been heavily restored. Unlike Statue 55 from Petworth previously described, the alterations, additions and modifications conducted upon the Wilton House collection are relatively easy to identify, no additional program of aesthetic restoration having been conducted upon the pieces to date.

In the portrait, only the bulk of the face, the forehead and fringe, cheeks, eyes, base of the left ear and top of the neck and part of the right side of the head and mouth survive, the back of the head, most of the hair, right ear, most of the left ear, nose, chin and neck all having been restored in marble, further patches of plaster repairing damage to the cheek bones, forehead, right eye and upper lip.

A slight but detectable blurring to the surviving hair and facial features suggests that the head has been extensively cleaned, possibly with acid (Peter Stewart pers. comm. 2009). The use of chemicals was an accepted conservation practice for marble statues in the 16th and 17th century, hydrochloric or sulphuric acid helping to strip away perceived impurities or encrustations and smooth out irregularities. Such extreme cleaning methods also had the unfortunate effect of creating either a soapy, weak surface (hydrochloric acid) or a pitted, porous one (sulphuric acid), which superficially made the face appear more polished but which in reality destroyed the surface (Fejfer 1997, 8), erasing the accumulated history of each piece.

Facial features (Figure 9), especially the eyes, are, despite later cleaning methods, crisply defined beneath thin eyebrows. The lips have been completely removed together with the nose and chin, although slight dimples remain at the corners of the mouth. Cheeks are fleshy and lacking in bone structure and the original nature of the chin is unknown. The coiffure, where it survives, is well defined and low on the forehead, the rather heavy fringe parted in a shallow V, just over the inner edge of the left eye. Sideburns delicately curl over both ears merging into a lightly incised beard that extends around the cheeks to the underchin and which has been continued, as it probably was originally, in the 17th century restoration. Thick comma-shaped locks fall in waves away from the restored crown and in long forward-combed strands on the nape of the neck.

The Wilton head appears to have been dislocated from the neck with force, blows from an axe or other iron-bladed implement impacting upon the right side of the neck, below the right ear, additional blows separating the back and further fragmenting the face. Sporadic battering to the face, removing the nose, upper lip and chin, and damaging the eyebrows, has also disturbed the cheeks and right eye, six discrete areas being rather crudely repaired in plaster. Unfortunately, as with Petworth Statue 55, the total absence of information regarding the nature of discovery and exhumation of the Wilton bust means that it is not known whether such trauma patterns relate to violence sustained during the initial overthrow of the portrait, its subsequent reuse, burial, or indeed to the techniques of 17th-century excavators and restorers.