Centre for the History of Emotions, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Sydney, Australia.

Email: kimberley.knight@sydney.edu.au

Cite this as: Knight, K. 2016 Hair in the Middle Ages, Internet Archaeology 42. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.42.6.10

During the Middle Ages hair was charged with cultural meaning. Hair possesses various qualities that allow it to be a tool of social action; it is detachable, renewable and can be manipulated (Firth 1973). As a malleable body part it can be shaped, dyed, and removed so the treatment of hair is a pre-eminently socially visible act (Bartlett 1994). Hair can convey messages of social differentiation. During the medieval period, as at other times, hair was variously deployed as a marker of status, race, physical maturity, and sexual virility (Mills 2004). Hair also played an important role in medieval religious life. From the 7th century, the tonsure designated clerical status and reflected the theological notions of submission and self-denial. The tonsure became such an important marker of status that by the 11th century it was required by ecclesiastical law (Council of Toulouse 1119; Mills 2004, 111). Similarly, later medieval holy women including Clare of Assisi (d.1253), Catherine of Siena (d.1380), and Columba of Rieti (d.1501) were known to have cut their hair as a sign of devotion (Bynum 1987, 146).

Conversely, the pileous saint became particularly popular during the high and later Middle Ages. First I will examine the connection between hirsutism (the abnormal growth of hair) and holiness, and then explore the contexts in which detached hair was an important bearer of meaning. Locks of saints' hair were venerated as relics and revered for their miraculous power, while the tresses of lovers were clipped and given as gifts that symbolised emotional bonds.

In the later Middle Ages in western Christendom, legends and images of anchorite saints who became hairy, like beasts, increased in popularity, as fleeing from the corrupt world, in the image of the desert fathers, was encouraged. These hirsute penitent saints are found considerably earlier in the East than West (Husband 1980, 98). Stories of holy men and women who had grown wild as a consequence of their isolation stemmed from the Apophthegmata Patrum (an influential collection of over a thousand stories and sayings of the Desert Fathers, dating from late 5th or early 6th century), and had affinities with eastern pre-Christian traditions (Williams 1926, 116). One of the Church Fathers, John Chrysostom (d.407), is an extensively represented hairy saint. From the 15th century, the image of John as a wild hirsute creature appeared in the West with remarkable frequency, although there appears to be no connection between the historical theologian and the later apocryphal legend in which the saint flees to the desert to avoid sexual temptation (Husband 1980, 102). Similarly, the legend of the 4th-century hirsute saint Onuphrius originated in the East but emerged in the West in the 13th and 14th century in Italy and Spain, before thriving in Northern Europe in the 15th century (Husband 1980, 98). Onuphrius was the son of a noble pagan ruler who doubted his legitimacy and tested him in a trial by fire. The young boy survived unharmed, and spent the first part of his life in an Egyptian monastery. When he reached maturity, Onuphrius left the monastery to pursue the life of a recluse in the wilderness near Thebes. He remained naked in the desert for seventy years and grew thick hair to protect his body against the elements. Mistaken by hunters for wild animals, these hirsute saints are often chased, a metaphor for the saint's pursuit of spiritual salvation (Husband 1980, 97).

Several pileous female saints also became particularly popular in the West during the later Middle Ages. Penitential saints, including Mary of Egypt and Mary Magdalene, who were believed to be guilty of sexual impropriety, were identified by their wild, flowing hair, which became a symbol of their repentance (see Husband 1980, 95-109; Figures 1-3). Mary Magdalene, who washed the feet of Jesus with her tears, and wiped them with her hair (Luke 7:38), appears in 13th-century depictions with a thick coating of hair, and it seems that her vita was conflated with elements of the life of Mary of Egypt, a harlot saint from Alexandria who withdrew to the desert to avoid sexual temptation (Pouvreau 2013). In later medieval images both saints are depicted covered with hair which conceals and protects the flesh, while simultaneously acting as the boundary between the interior and exterior (Pouvreau 2013, 191). In these legends the purity of the soul is contrasted with the bestial nature of the flesh.

Hair was among the first type of relic to be collected from holy bodies because, along with fingernails and teeth, they were the only parts allowed to be taken on theological grounds. Until the 9th century there was a desire to keep the body of saints whole, but hair could be taken as it was deemed to be superfluous, and an element that continued to grow after death (Angenendt 2011, 22-3). When the reluctance to divide up a saint's body waned, hair continued to be an important relic. Revealing the incorruptible body of a saint was crucial in the legitimisation of sanctity and the establishment of a cult. The uncorrupted body of a saint was interpreted as a sign of grace and reflected the imperishability hoped for in the Resurrection (1 Cor. 15:42; Angenendt 2011, 221). It was often the perfectly preserved hair of an exhumed saint that provided evidence of their holiness, and rebuffed potential detractors. One of the earliest biographers to refer to the cult of relics, Ambrose's biographer Paulinus recorded that when the early Christian martyr Nazarius was disinterred at the end of the 4th century, the saint's hair was perfectly preserved, and 'not a hair on his head had been lost' (Lk. 21:18) (Snoek 1995, 3202). Finding the unspoiled hair of a saint during their exhumation became a hallmark in the formation of a cult.

When the coffin of the first Christian king of Norway, Ólaf Trygvasson (d.1000), was disinterred twelve months after his passing, those present observed a great change in the former king's hair and nails: they had grown almost as much as if he had been alive. The beard and hair were subsequently trimmed and put into the fire in order to ascertain whether they could be deemed holy relics. When the bishop took the hair out of fire, it had not burned. Ólaf was then officially declared a saint and miracles began to take place at his shrine (Ađalbjarnarson 1945, 404-5). Like other types of relics, hair had a prophylactic power. The hair of Hildegard of Bingen (d.1179) was preserved in a small silk casket (pyxidula serica) on the altar and when a fire swept through the church, the relics were found to be unharmed by the flames (Bruder 1883, 1233; Figure 4). The hair of saints also had the power to work miracles before and after death. The life of the beguine (a member of a lay religious order) Marie d'Oignies (d.1213), written by her confessor Jacques de Vitry c.1215, records the story of a man who, despite being attended to by a number of doctors, was told to await his death because nothing could be done to alleviate his sickness. However, the man received health by the touch of Marie's hair (ad tactum capillorum eius recepit sanitatem) (Huygens 2012, 1074). Furthermore, hair relics had apotropaic powers. A single hair of Hildegard of Bingen had the power to arouse protest from a demon who was plaguing a woman (Bruder 1883, 1245).

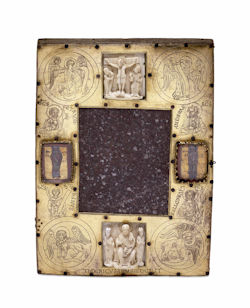

Hair relics needed to be carefully preserved because of their delicate nature. The Middle Ages saw the proliferation of lavish, bejewelled reliquaries in which to house the precious remains of saints. Their spectacular appearance highlighted their importance as repositories of spiritual power.

Magnus the Good, King of Norway (r.1040-1047), had a reliquary made to contain the hair and fingernail relics of his saintly father Ólaf. The relic box was adorned with gold and silver and inlaid with precious stones (Ađalbjarnarson 1951, 20). The sumptuously decorated Hildesheim portable altar (c.1190-1200) contains the relics of forty saints, each of whom is named on the reverse. The accumulation of relics in a single piece served to increase the altar's sacredness, and numbered among its contents is the hair of St John the Evangelist, wrapped in textile and carefully labelled. The portable altar was a way of reaching remote places or those who could not go on pilgrimages. In this way, many people could come into contact with the holy material treasured inside. Charlemagne (d.814) is also said to have possessed a portable hair relic. Known as the 'Talisman of Charlemagne', the pendant reliquary was crafted from gold and encrusted with filigree, pearls, garnets, emeralds and a large sapphire (Robinson 2011, 113; Figure 5). An inventory from the 12th or 13th century suggests that the amulet contained the hair of the Virgin Mary (Robinson 2011, 113). Relics of the Virgin were believed to be rare, owing to her assumption into heaven, so fragments of her hair, breast milk and clothing were particularly precious.

The popularity and ubiquity of hair relics in the high and later Middle Ages is attested in English relic catalogues, often drawn up by larger churches. In a list of ornaments dated to 1316, the Cathedral Priory of Christ Church in Canterbury claimed to possess the hairs of St Anne, mother of the Virgin Mary; St Cecily, an early Roman martyr; St Edmund Rich, the former Archbishop of Canterbury (r.1233-40); St Francis, founder of the Franciscan order (d.1226); Laurence, a 3rd-century martyred archdeacon from Rome; Peter the Apostle, and Thecla, the first disciple of St Paul (MS Cotton MS Galba E IV, ff. 122v-127v; Thomas 1974). Similarly, a list compiled at St Cuthbert's Shrine in Durham in 1383 describes how the church possesses 'the hair of a great many saints' (de capillis plurimorum sanctorum), including two relics with hair of Mary Magdalene; the hair of the abbot St Bernard in a purse with a shield; hair from St Bartholomew; pieces of rib and hair from St Bernard; the hair of the venerable Robert de Stanhope; the beard of St Goderic; and some cloth and hair from St Boisil the priest (Fowler 1899, 426-356). In addition to the devastation of the Reformation, the chemical fragility of hair means that it is rarely preserved (see Ashby, this issue). Consequently, reliquaries leave no traces of the hair they were said to contain, even those as famous as the Talisman of Charlemagne.

It is evident that hair was an important bearer of meaning in the context of medieval religious life; however, the adoration of hair was not limited to the sacred. During the later medieval period locks of hair were potent symbols of romantic love and the growth or clipping of hair could communicate powerful emotional statements.

Hair is a part of the body that can be easily detached and transferred to another person and thus it could be transformed from a raw material into a love token. The cutting of hair in order to make a token of affection was a strong personal and emotional statement. The 14th-century French romance of the Castelain de Couci et de la Dame de Fayel describes how locks of hair were exchanged by lovers before a departure (Petit and Suard 1994; see also Sleeman 1981). A lock of hair was a piece of the person who was left behind; it became an emotional aide memoire for the recipient and kept the lovers connected during times of absence. While hair could be clipped before a departure, its growth could also symbolise the length of time that lovers had been apart. In the poetry of Chrétien de Troyes, written in the 12th century, men refused to shave their beards until they were reunited with their beloved (for the symbolism of beards not being removed, see Ashby this issue). Finally, hair was an intimate element that engaged the sensory mode. In Chrétien de Troyes' Knight of the Cart, Lancelot finds a comb that preserves some of the fair hair of Queen Guinevere. He presses the hair to his mouth and face, which induces feelings of joy and delight and stimulates his desire for Guinevere (Rogers 1984).

Hair offers many paradoxical readings. From the rough covering of hirsute saint's skin to the delicate tresses of a lover, hair could both shield the body and deny sexual temptation yet, in other instances, stimulate erotic desire. The multiple qualities of hair and the diversity of 'hair behaviour' (see Ashby, this volume), allow it to convey many different meanings and its reading remains highly contextualised. In the cases presented here, hair was prized in both sacred and secular contexts: it was venerated by the faithful, cherished by lovers, and a powerful symbol of flight from the world.

I wish to thank Julian Luxford for providing me with a copy of Islwyn Geoffrey Thomas' wonderful unpublished thesis on relic lists in medieval England. In addition, I would like to thank John Shinners and Genevra Kornbluth from the Medieval Religion discussion list for drawing my attention to the hair relics in the Durham account roll and the Talisman of Charlemagne respectively. Finally, I am grateful to John Hudson for his continued support and encouragement.

Dr Kimberley-Joy Knight is the recipient of an Australian Research Council Post-Doctoral Fellowship (project number CE110001011).

Ađalbjarnarson, B. (ed.) 1945 Snorri Sturluson, 'Óláfs saga Helga', Heimskringla volume 27, Reykjavík: Hiđ Íslenzka fornritafélag.

Ađalbjarnarson, Bjarni (ed.). 1951 Snorri Sturluson, 'Magnúss saga ins góđa', Heimskringla volume 28, Reykjavík: Hiđ Íslenzka fornritafélag.

Angenendt, A. 2011 'Relics and their veneration' in M. Bagnoli, H. A. Klein, C. Griffith Mann, and J. Robinson (eds) Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe, London: British Museum. 19-28.

Bartlett, R. 1994 'Symbolic meanings of hair in the Middle Ages', Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 6(4), 43-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3679214

Bruder, P. (ed.) 1883 'Acta inquisitionis de virtutibus et miraculis S. Hildegardis', Analecta Bollandiana 2. 116-129.

Bynum, C.W. 1987 Holy Feast and Holy Fast: the religious significance of food to medieval women, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Firth, R. 1973 'Hair as a private asset and public symbol' in R. Firth Symbols: Public and Private, Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 262-298.

Fowler, J.T. (ed.) 1899 Extracts from the Account Rolls of the Abbey of Durham, Surtees Society 100(2), Durham: Andrews & Co.

Husband, T. 1980 The Wild Man: Medieval Myth and Symbolism, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Huygens, R.B.C. (ed.) 2012 Iacobus de Vitriaco, Vita Marie de Oegnies, Turnhout: Brepols

Milliken, R. 2012 Ambiguous Locks: an iconology of hair in medieval art and literature, London: McFarland & Co.

Mills, R. 2004 'The signification of the tonsure' in P.H. Cullum and K.J. Lewis (eds) Holiness and Masculinity in the Middle Ages, Toronto: University of Toronto. 109-126.

Petit, A. and Suard, F. (eds) 1994 Le livre des amours du châtelain de Coucy et de la dame de Fayel, Lille: Presses de l'Université.

Phelpstead, C. 2013 'Hair today, gone tomorrow: hair loss, the tonsure, and masculinity in Medieval Iceland', Scandinavian Studies 85(1). 1-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.5406/scanstud.85.1.0001

Pouvreau, F. 2013 'Pilosa sum, sed formosa: Corps Stigmatisé et Sainteté Admirable dans l'iconographie des Saints Ermites velus au xve siècle (1410-1530)' in M. Guay, M. Halary and P. Moran (eds) Intus et foris: une catégorie de la pensée médiévale? Paris: Presses de l'Université Paris-Sorbonne. 185-200.

Robinson, J. 2011 'From altar to amulet: relics, portability, and devotion' in M. Bagnoli, H.A. Klein, C. Griffith Mann and J. Robinson (eds) Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe, London: British Museum. 111-16.

Rogers, D. W. (ed). 1984 Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart: Chrétien de Troyes. New York: Columbia University Press.

Sleeman, M. 1981 'Medieval hair tokens', Forum for Modern Language Studies 17(4). 322-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/fmls/XVII.4.322

Snoek, G.J.C. 1995 Medieval Piety from Relics to the Eucharist: A Process of Mutual Interaction, Leiden: Brill.

Thomas, I.G. 1974 The cult of saints' relics in Medieval England. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of London.

Williams, C.A. 1926 'Oriental affinities of the legend of the hairy anchorite', University of Illinois Studies in Language and Literature 11(4). 429-510.

The comments facility has now been turned off.

Footnote 1: 1 Cor. 15:42: sic et resurrectio mortuorum seminatur in corruptione surgit in incorruptione (So also is the resurrection of the dead. It is sown in corruption: it shall rise in incorruption).

Footnote 2: Lk. 21:18 : et capillus de capite vestro non peribit (and a hair of your head shall not perish).

Footnote 3: Petrus Bruder (ed). 1883 'Acta inquisitionis de virtutibus et miraculis S. Hildegardis' in Analecta Bollandiana, 2, 116-29 at 123: 'Willhelmus (.) cui cum crines beatae Hildegardis dati pro reliquiis essent, et in pyxidula serica recondisset (.) ecclesia et iis quae erant altari, exustis, pyxidula serica permansit illaesa'.

Footnote 4: Huygens, R.B.C. (ed). 2012 Iacobus de Vitriaco, Vita Marie de Oegnies. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, liber 2, p. 107:'Quidam etiam, de cuius infirmitate omnes desperabant, ipse etiam, cum multos medicos attemptasset et nichil profecisset et non nisi mortem expectaret, ad tactum capillorum eius recepit sanitatem'.

Footnote 5: Petrus Bruder (ed). 1883 'Acta inquisitionis de virtutibus et miraculis S. Hildegardis' in Analecta Bollandiana, 2, 116-29 at 124: 'Ipsa vero partem crinium suorum eidem tradidit; et illa secundum ejus mandatum suis crinibus innexuit. Quod daemon sentiens, marito dixit: 'Me decepisti; nihil juris in ea habeo propter incantationes Hildgardis'.'

Footnote 6: J. T. Fowler (ed). 1899 Extracts from the Account Rolls of the Abbey of Durham, Surtees Society 100(2) Durham: Andrews & Co.: Item una (p. 427) fiola cristallina cum capill. et peplo Sce. Marie Magdalene . et una petra aquile et crines Sce. Marie Magdalene. . et de capill. Sci Bernardi abbatis in bursa cum scutis varii coloris ut supra. et de capill. Sci Bartholomei eremite de Farne et monachi Dunelm in fiola cristallina. Item cophin [sic] cum capill. et cilicio venerabilis Roberti de Stanhope (p. 428) . Item de barba Sci. Godrici. . particular de costa Sci Bernardi abbatis et de capillis ejusdem . (p. 430) et de vestibus et capillis Sci. Boysili. (p .434) Item de capillis plurimorum sanctorum .

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.