Cite this as: Halle, U. and Hähn, C. 2024 Archaeology and the Public Perception of a Soviet Prisoner of War Cemetery, Internet Archaeology 66. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.66.18

The Free Hanseatic City of Bremen is situated in north-west Germany and its modern state constitution was declared on 21 October 1947. Bremen was then an American Enclave in the British occupation zone and consisted of the two cities of Bremen and Bremerhaven. Today, it still consists of both cities and is the smallest federal state of Germany.

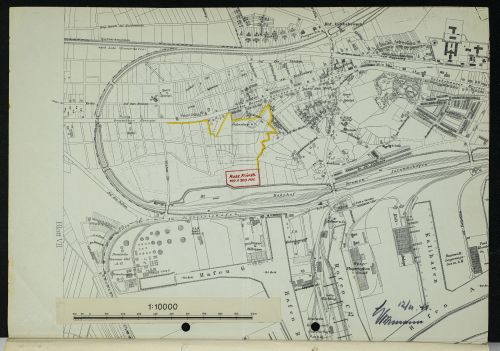

During World War II and after the invasion by the Soviet Union, Bremen called for a greater number of POWs to work in the harbours, the armaments industry and communal daily tasks, e.g. waste sorting (Letter 19.11.1941). The first few hundred Soviet POWs brought to Bremen were in such poor condition that many of them died in the first weeks after their arrival. The government then had to create a burial place, which written sources suggest was built at an accelerated tempo, but nevertheless, in accordance with general politics, in an abandoned area far away from the public eye but close to the camp (about 350m). The camps and the cemetery were located in a district of Bremen then called Grambke, today known as Oslebshausen (about 4km north-west of the centre of Bremen). On 12 November 1941, an area of up to 20,000m² was planned for the cemetery (Projected Plan 1941; Figure 2) but by 17 November 1941, only 3500m² was created (Figure 4).

The numbers of dead POWs decreased slowly in all the camps on the Reichsgebiet after February 1942 because of a change in food provision (after the death of a higher number of POWs: Keller 2011, 346-49). This overall situation is reflected in the cemetery in Bremen where single and double burials or at least smaller group burials were carried out except for special incidents. The cemetery was in use until the end of the war in April 1945. Owing to a lack of documentation, papers and reports from that time period relating to the cemetery and its first (as we now know) imperfect exhumation, the total numbers of dead buried here remains unclear.

After consultations in the summer of 1947, the cemetery was exhumed a year later by decision of the Bremen Parliament and Senate. The human remains of '446 dead' (Weser Kurier 1948) were buried afterwards as 'unknown dead' in the honorary cemetery in Bremen-Osterholz in a mass grave field for war dead with a permanent right of rest. It seems that no documentation of this exhumation was carried out, except for this small notice in the press. No attempts were made to identify the dead. Reflecting the post-war situation in Bremen, the excavation and first attempts to conduct historical research reflected the general practice relating to extant burials of Soviet Prisoners of War, which can be described as 'accord-like extraction of bones, paying no attention to bodily integrity' (Hausmair et al. 2020, 4). Right after the exhumation, the site of the cemetery was filled with World War II debris in a layer up to 2m thick collected from around the city. In the 1970s, an industrial compound was built on parts of the site (Figure 1a and b).

During the 1990s, local groups started to commemorate the cemetery and the forced labour camps in the district. In this regard, an Orthodox cross was erected on public ground about 400m away from the site of the cemetery and camps (Figure 1a). The remaining area of the former cemetery was used as a storage yard for stones and construction materials. The Orthodox parish took care of the memorial place but the former cemetery was no longer remembered.

At the beginning of 2021, investigations by two citizens' initiatives opposed to development and construction plans revealed the location of the former cemetery in the area of the dock railway in Bremen-Oslebshausen and brought it back into public and political consciousness.

Prior to the excavation, the Landesarchäologie was able to gain evidence about the location of the cemetery by inspecting aerial photos of the area taken by Allied military aircraft between January and March 1945. Based on these aerial photos, the cemetery could be georeferenced during spring 2021. This analysis also revealed that the size of the cemetery was not as originally projected, but that there was only 3500m² of fenced-in area directly next to the railway embankment (Figure 4). An additional investigation, analysing the four-camp-zone in the south-western half of the horseshoe-shaped railway curve of Oslebshausen (Nnamdi 2022a, Figure 3) revealed the spatial correlation of the cemetery and the four forced labour camps in an area dominated by industry and ports.

Since May 1946, the Arolsen Archives had kept a very precise description made by a police officer from Oslebshausen by order of the United Nations (Schenk 1946). This record describes the cemetery as an area 'fenced with barbed wire, with three different areas'. The police officer recorded 217 graves with numbers and noted that these numbers had to be read on wooden signs on the graves from top to bottom. Furthermore, graves with the designations Z1 to Z63 were still present and he also recorded two graves by name.

After the aforementioned georeferencing by aerial photographs, the remains of the cemetery were excavated archaeologically. By excavating the site, a closer look at the exhumation would show how many burials were originally situated here. At first only empty burial plots were expected. After the excavation cleared the site of the former cemetery, the site would have been sanctioned for construction.

The excavation started with one month of preliminary works on 1 July 2021 and ended on 11 November 2022. During the course of the excavation, the remains of the aforementioned fence as the boundary of the cemetery infrastructure were documented. The preliminary work also revealed that about a third of the 3500m² of the cemetery was already heavily built upon and therefore destroyed. Owing to the excellent bone preservation on the complete site, fragments of human skeletons were found in each of the exhumed burial pits and a total number of 66 complete skeletons were recovered in several burial pits, including five mass grave contexts. Of particular importance was the discovery of c.200 metal POW ID tags, which the Landesarchäologie is currently restoring. These objects should allow us to identify more than 150 people who were originally buried here.

By matching the numbers stamped on the ID tags with the publicly accessible OPD Memorial database of POWs from the former Soviet Union, which is located in the Russian Ministry of Defence, one of the tags was able to be assigned to the Ukrainian soldier Iwan Pasternak (Figure 5). A joint project with the Tarras Shevchenko University in Kyiv (a two-week collaboration with four students and a historian from Kyiv on the excavation site in September 2021; Kuleba 2022) was organised by the Bremen States Chancellery in cooperation with the Ukrainian Consulate General in Hamburg. Thanks to this contact, the Landesarchäologie was also connected to scholars from the National Museum of History of Ukraine in the Second World War near Kyiv, where we sent the dates and name of Iwan Pasternak. The scholars there were able to locate direct living descendants of Iwan Pasternak very quickly and the Landesarchäologie gained more details about the life of this victim.

Iwan Pasternak was born on 8 June 1908 in a small village about 40km west of Lviv. He trained as a tailor and married Sydonia Stepanivna Sytnyk in 1933 (Figure 6). Their son Oleg was born in 1936 and their daughter Maria in 1937. Maria was the person who conveyed the facts and provided this photo to the museum in Kyiv. The museum then sent the information to the Landesarchäologie. Pasternak's family members gained knowledge about the fate of their father and grandfather in 2021, 80 years after the German Wehrmacht attacked the Soviet Union. They learned that he was a POW, the date of his death in Bremen and an idea of where his grave is today.

Clearly, this excavation had a special political dimension even before it began. Its major task had been to clarify the function, condition and the dimensions of the site by excavating it precisely and scientifically. The results should have generated a neutral basis for further discussions and construction plans. Moreover, it should have been one step in the reconciliation of the conflict between the citizen's initiatives and Bremen's senate - a role in which it did not succeed.

From the beginning of the excavation, it became clear that the archaeological project played a role in the ongoing process of dealing with National Socialism in Bremen and Germany. Reappraising the World War II and post-war period's relations between the successor states of the Soviet Union and Germany was one of the reasons for the national and international media interest. This made the continuous public relations work during this excavation essential, and consisted of up to three media events or public appointments per week (Figure 7).

One citizens' initiative ('Bürgerinitiative Oslebshausen und umzu') consisted of residents of Bremen's districts Grambke, Gröpelingen and Oslebshausen, and was committed to the quality of life and living in these districts. A second one, the 'Peace Forum' ('Friedensforum'), also saw itself as a citizen action committee, and part of the worldwide peace movement, declaring itself as independent of parties and organisations. Both these groups drew public and political attention to the cemetery and continue to observe the excavation and the analysis. Other projects of the Landesarchäologie, within the context of the archaeology of modernity, also attract their attention, and they view the Landesarchäologie as one of the conflict parties around the former POW cemetery rather than a neutral research institution.

In February 2021, both groups demanded that the Landesarchäologie designate the exhumed cemetery as an archaeological monument, following the example of the KZ-subcamp of Neuengamme, the so-called 'Schützenhof' in Bremen-Gröpelingen (Halle and Huhn 2019). After researching more information about the site of the cemetery, it became clear that it would be impossible to include it in heritage protection because it was presumed that the remains had already been interred and therefore resolved. The two citizen groups then claimed (in different press releases) that they estimated between 1,000 and up to 10,000 POWs were still buried in the 20,000m² of the area projected by the NS-government. In July 2022, after consultation with the local politicians, and the Russian and Ukrainian Consulate, the Landesarchäologie scheduled and instigated the official excavation of the cemetery.

When the preliminary excavations started, the citizen groups informed Bremen's politicians and the responsible embassies of the Russian Federation and Ukraine of their objections. In these letters, the two groups described Bremen's Senate as 'unconcerned with history' (in German 'geschichtsvergessen') and put the local politicians and the Landesarchäologie on a par with the Nazis (Hethey 2021; Winge and Lentz 2021). The verbal attacks continue to this day and are spread via the press and internet.

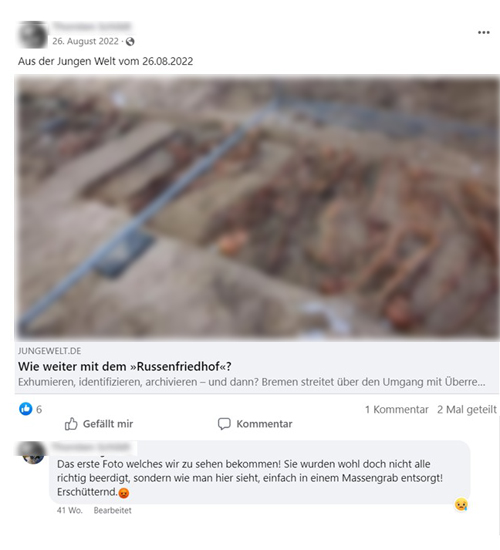

Right at the beginning of the excavation, the Landesarchäologie decided that no photographs of human remains would be given to the public. By this imperative, we followed the Guidelines on the Care of Human Remains in Museums and Collections (Deutscher Museumsbund 2021).

Even on memorial sites dealing with the NS-past in Germany, it can sometimes be the case to show pictures of human remains (not for shock value and always on a small scale) (Wehling 1977; Matzen 2007; BPB 2011). However, in this instance it seemed necessary to prevent the invasion of personal privacy of the buried individuals by not showing pictures without the consent of their existing living descendants.

Most of the media reports dealt with the topic objectively and respectfully but some media were influenced by the two citizen's initiatives did not do so, as Figure 8 demonstrates.

We assume that a photo of the first uncovered mass grave was obtained, leaked to the press (Werner 2022), and then linked with the following comment on their Facebook page: 'The first photo we get to see!' The 'Friedensforum' used the same picture two months later in a press release (Pressemitteilung 2022b), where it remains online today.

The groups are demanding the photos and the list of identified ID tags from the Landesarchäologie rather than wait for the scientific evaluation to be completed with the measures of the Landesarchäologie being perceived as 'censorship' (Lentz and Winge 2022, 14, point 4). During the excavation, the Landesarchäologie offered six public guided tours, visited mostly by inhabitants of the neighbourhood, accompanied more than 20 international media visits and made it possible for nine school classes to visit the excavation. More than 120 guided visits of different groups from politicians and memorial sites were organised. The first results and finds of the excavation are part of a current exhibition in the Focke Museum, Bremen's Museum of Art and Cultural History. The exhibition was developed by groups of the urban civil society. In October 2022, the Landesarchäologie held an orchestral concert with a symphony by Reinhold Glière and the song 'Cranes' by Yan Frenckel to mark the official completion of the excavation. Both groups protested in front of the concert with banners and flyers where the aforementioned photo of the mass grave was again shown (Figure 9).

In a letter to the consulate of the Russian Federation in December 2022, the groups claim that archaeologists have 'abandoned' the excavation and are not investigating the area completely. This shows that they are not taking into account our methodology nor the first results of the archaeological excavation which was completed with accuracy and without time constraints. Indeed, a 'best practice' had been established that can be used as an example for similar projects in the future, and all the excavated material has been sieved to collect even the smallest bones that had been spread by the exhumation activities.

As the Landesarchäologie has communicated in letters and in the media, archaeological monitoring is mandatory in the event of any upcoming construction measures anywhere close to the former cemetery.

Further scientific research, including a bioanthropological evaluation of the human remains is planned. When the excavation finished, the two successor states of the former Soviet Union decided that the excavated remains should be buried in the same central municipal cemetery of honour for all POWs and victimes of concentration camps and bombing where the remains that were exhumed in 1948 are located. The timeframe depends on completing the research on the human remains and on diplomatic commitments with the involved former Soviet States (especially Ukraine and the Russian Federation) which clearly is complicated owing to the ongoing war at the time of writing.

From excavation to the current point of investigations and until the actual reburial, the Landesarchäologie has taken responsibility for the human remains. This entailed that pictures of human remains were not shown in public. In the context of interaction with parts of civil society, the individuals represented by the human remains, ID tags and personal items can be viewed as victims in past, present and future contexts, not only during the National Socialist era (see Metten 2022 and related videos).

The notion of 'victims' has several connotations and the use of the word 'victim' as an identity can have different implications, depending on who is using it, claiming it, rejecting it or attributing it to others. Why does the Landesarchäologie see the deceased as victims of multiple contexts? We differentiate them as victims of different times and of different groups.

The German Wehrmacht was responsible for the food and nutrition, for conditions of accommodation and for guarding POWs. Many Soviet POWs died of malnutrition, disease, unhygienic conditions, lack of medical care, and violence at the hands of the guards. The profiteers of forced labour enriched themselves at the expense of the POWs. In Bremen's cemetery in winter 1941-42, most of the dead were not given individual plots but were buried in mass graves. From spring 1942 onwards, the dead were buried mostly in individual graves, but sometimes in an irregular manner.

Between May 1946 and the autumn of 1948, the wooden signs that marked the burials were lost. During the exhumation in autumn 1948, many of the body parts of the dead were also lost. The workers treated the human remains in a very undignified manner, and they lost their identity for good, because during this process the ID tags did not stay with the corpses. Besides this, no attempts were made to document their identities e.g. via the numbers on the tags. The reburial took place in a cemetery of honour in autumn 1948 but there they were reburied as unknown dead.

In West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s, during the Cold War, Soviet cemeteries were perceived as 'provocations' and 'monuments of shame' (Davydov and Hanke 2013, 111; Weidner et al. 2020, 302). Mostly they had not been accepted as places of remembrance for the Soviet victims of National Socialist crimes. Together with this obliteration of places went the neglect of Soviet POWs as one of the largest victim groups of National Socialism in Germany after the Jewish population. Here in Bremen, this reinterred cemetery and the unknown dead disappeared from public awareness, in the shadow of memory (Steinmeier 2021). Even at the Orthodox cross, erected in 1996, commemorative events rarely took place.

The groups that drew attention to the cemetery are still trying to achieve their purpose of preventing any construction at the site by operating against the Landesarchäologie. They use the former cemetery to try to reduce the probability of building which is why they claim that the Landesarchäologie has not fully examined the site. Both groups consider building on the former mass grave, which they call the 'Russian Cemetery', to be a renewed desecration, unworthy and, according to the applicable provisions of international law, not humanitarian (Pressemitteilung 2021). The overall tenor of their expressions is mostly dramatic with statements that are not necessarily true, yet Bremen's Law for the Protection of Monuments provides a way to monitor every construction activity by the Landesarchäologie.

Before the start of the excavation, the Landesarchäologie expected to be investigating empty graves. With the discovery of the first human remains, we developed an ethical code in which pictures of human remains would not be given to the media, and shown only to political leaders and the scientific community. We cannot bring the victims back to life, but we can give some of them their names back and thus their identity by means of our scientific research. The Office for War Graves Care and Remembrance Work at the Russian Embassy and representatives of Russia and Ukraine have been and will be involved in all issues of excavation and scientific research. All investigations are carried out with great respect for the dead and with a focus on living descendants, who may obtain information about their ancestors. Within the scope of the future research project, the Landesarchäologie plans to collect pathological and other data (via non-invasive research on the human remains) to gain evidence about the daily life in the camps during World War II.

After the scientific investigations, all remains of the Soviet POWs will be buried in the honorary cemetery in Bremen-Osterholz. Bremen will need permission from both Ukraine and Russia for the reburial of the human remains.

The aim of our research and a special task of this excavation is the identification of as many people as possible by restoring the ID tags recovered during the excavation and making them readable again. Because of the sandy substrate, most of the tags are in very poor condition and heavily encrusted. The Landesarchäologie Bremen hopes to be able to tell many more family members of Soviet POWs about the fate of their relatives and give them a place of mourning and remembrance.

This excavation project can serve as an instructive example for handling other apparently exhumed Soviet POW cemeteries in former Nazi Germany. With its scientific methods of documentation, field archaeology is a relevant instrument to approach such a problematic site in the context of heritage management. Nevertheless, further historical and bioanthropological research is necessary to create an overall picture and to gain the most societal and political benefits.

Thanks are due to Annika Böger, Jan Geidner, Hans Christian Küchelmann, the National Museum of History of Ukraine in the Second World War, Tetiana Pastushenko, Birgitt Rambalski and Werner Wick.

The excavation, documentation and processing of the documentation is funded via the costs-by-cause-principle after the 'Bremisches Gesetz zur Pflege und zum Schutz der Kulturdenkmäler (Bremisches Denkmalschutzgesetz - BremDSchG) vom 18. Dezember 2018 (Brem.GBl. 2018, S. 631)', 2. Abschnitt, § 9, Absatz 3.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.